12 Decision Trees

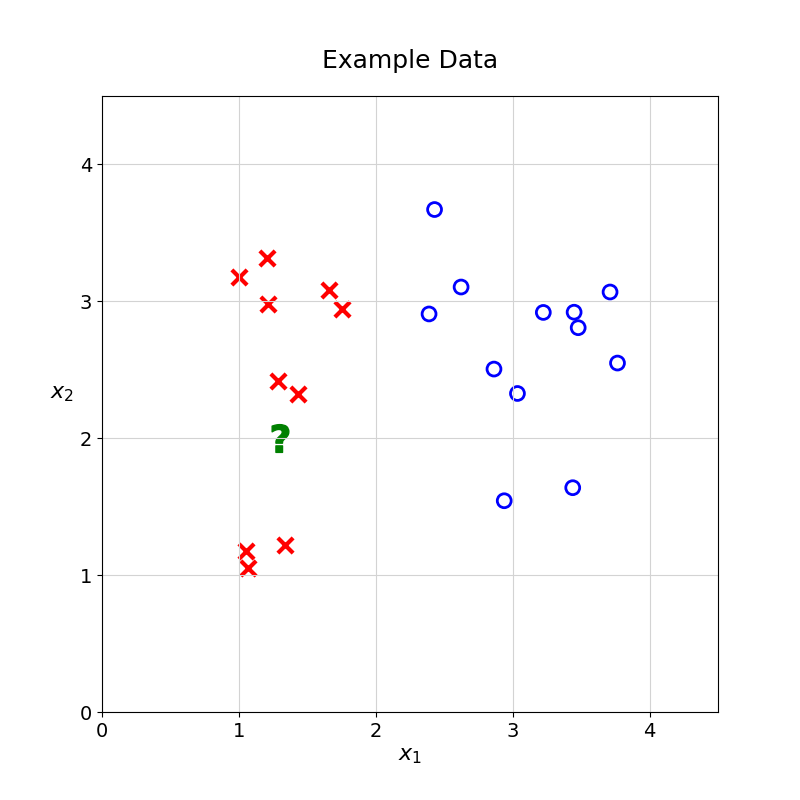

It is now time to introduce a second model architecture. How would you predict the class of the unknown observation without using distance functions or nearest neighbours?

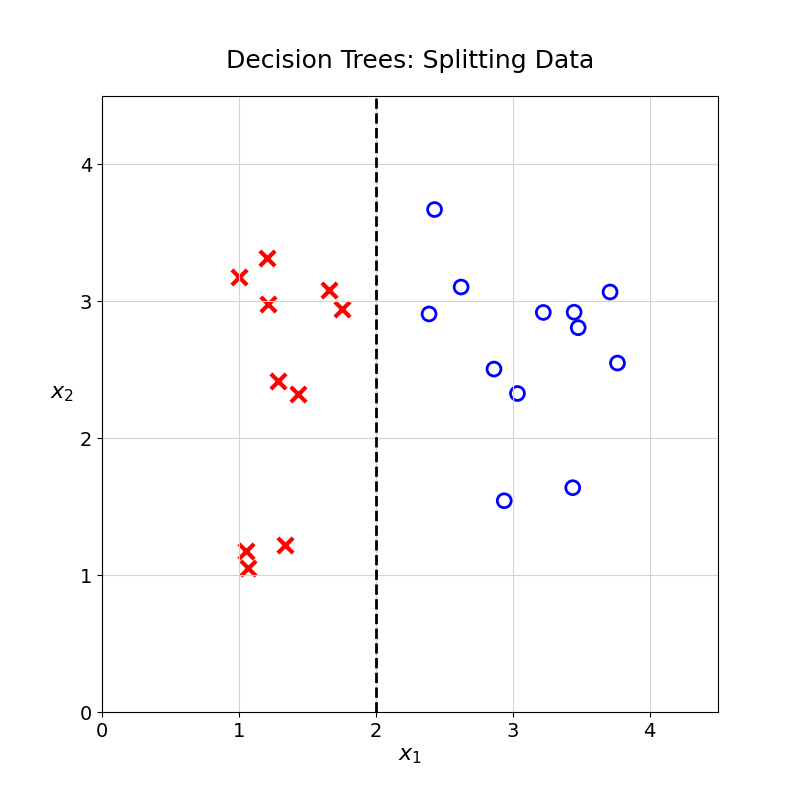

One possibility would be to split the data at \(x_1 = 2\). Any observation with \(x_1\) greater than \(2\) would be classified as \(\circ\); the rest would be classified as \(\times\).

12.1 Multiple Splits

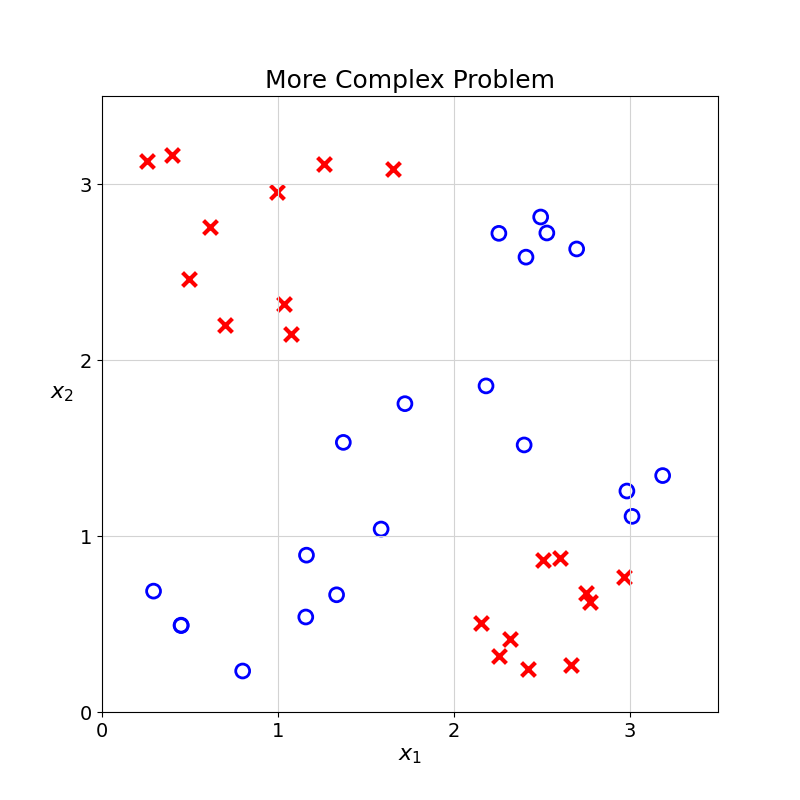

For a more complex case, how would you predict the class of the unknown observation with this training data? How would you split the \(\times\) from the \(\circ\)?

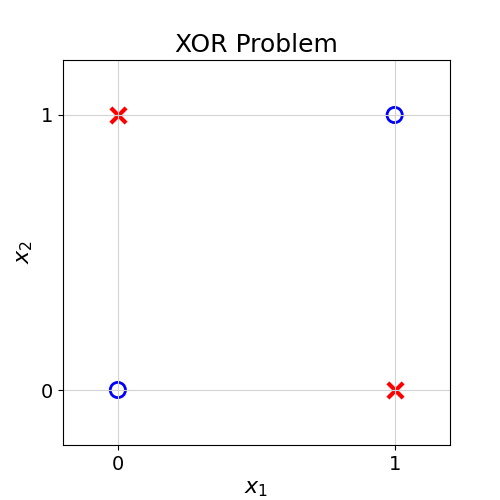

In this example, there is no single line that can perfectly split the two groups. In Computer Science, this is also called the XOR problem.

The XOR (Exclusive Or) Problem refers to a foundational Machine Learning and Computer Science problem in which two classes cannot be separated by any single straight line. It demonstrates the weaknesses of simple linear models.

The XOR is a logical operation that takes two Boolean (True/False or 1/0) values as inputs and returns 1 (or True) if they are different and 0 or False otherwise. You can see the truth table for this operation below.

XOR Truth Table

| Input A | Input B | Output (A XOR B) |

|---|---|---|

| False | False | False |

| False | True | True |

| True | False | True |

| True | True | False |

More information on the XOR problem at (“Exclusive Or,” n.d.)

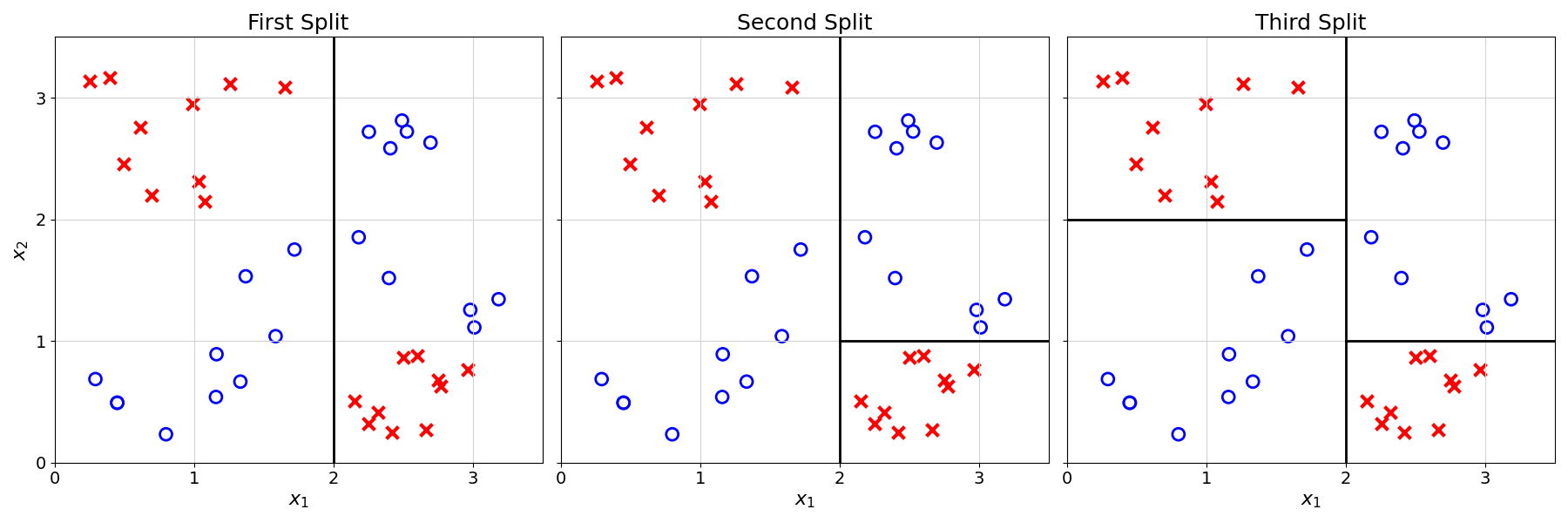

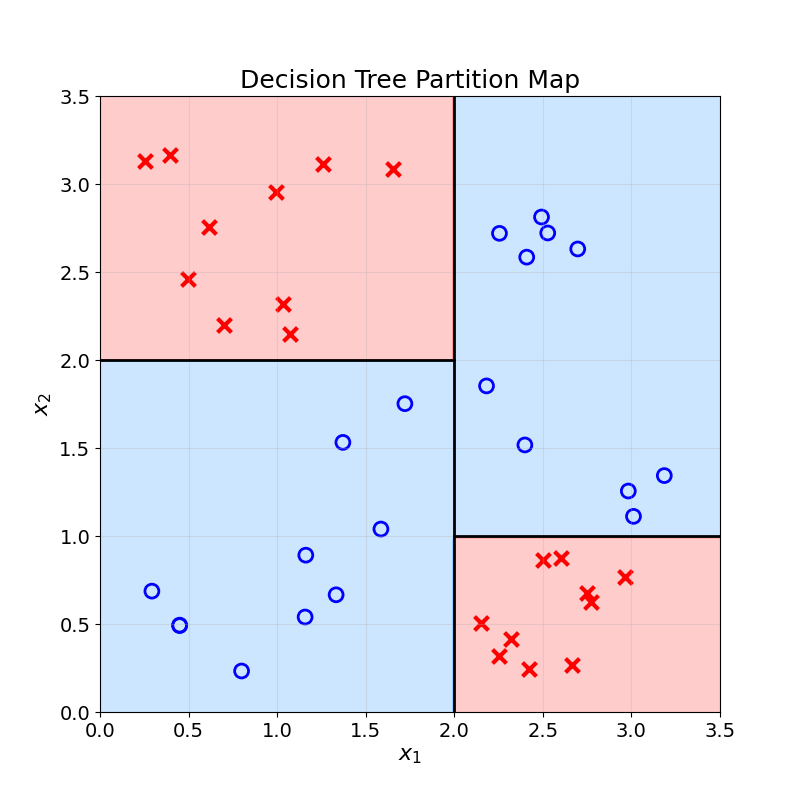

Instead of splitting the data once, what if you could split the data multiple times? An example is shown below:

12.2 From Splits to Predictions

Using these three splits, how could you classify a new observation?

One way to do so would be to go through the splits we did one by one:

- If \(x_1 \geq 2\):

- If \(x_2 \geq 1\): assign \(\circ\)

- Else: assign \(\times\)

- Else:

- If \(x_2 \geq 2\): assign \(\times\)

- Else: assign \(\circ\)

The observation is then assigned the label that is the majority in the resulting partition.

Exercise 12.1 Using the above list, generate predictions for the following observations:

- Observation 1: \(x_1 = 3,x_2 = 3\)

- Observation 2: \(x_1 = 1,x_2 = 3\)

- Observation 3: \(x_1 = 1,x_2 = 1\)

12.3 From Partition to Trees

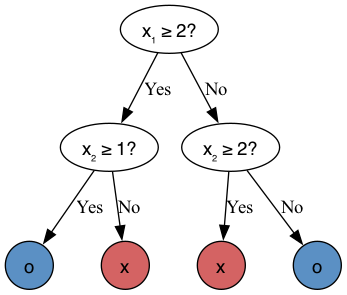

The above list may be difficult to follow. This type of logic could be more elegantly represented as a tree (also called a decision tree):

Exercise 12.2 Generate predictions for the following observations by going down the Decision Tree above:

- Observation 1: \(x_1 = 3,x_2 = 3\)

- Observation 2: \(x_1 = 1,x_2 = 3\)

- Observation 3: \(x_1 = 1,x_2 = 1\)

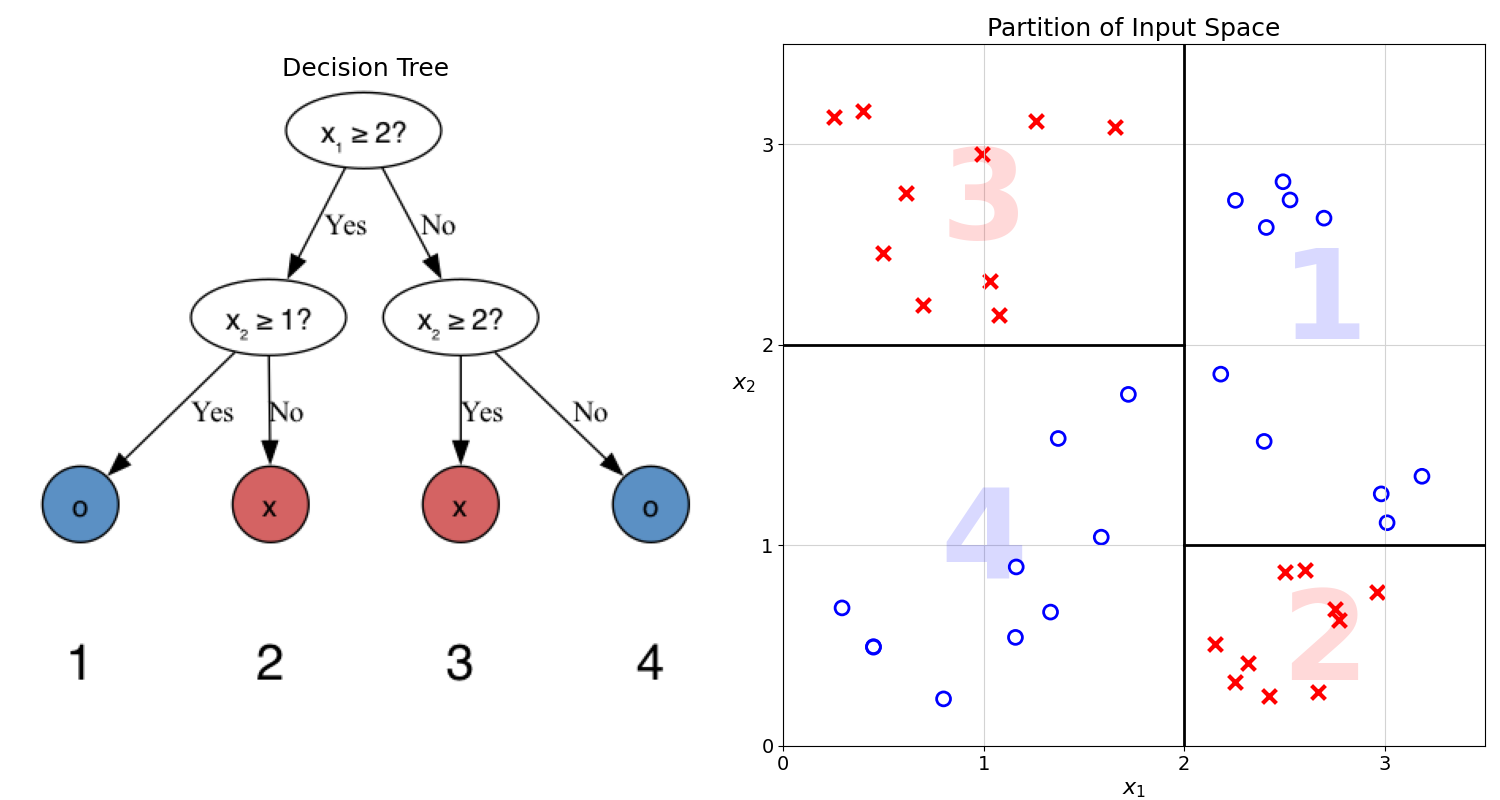

To better understand the relationship between trees and data splits, the tree and the partition can be visualised next to one another:

Each split or comparison creates a linear separation in the feature space, represented by a black line in the chart above.

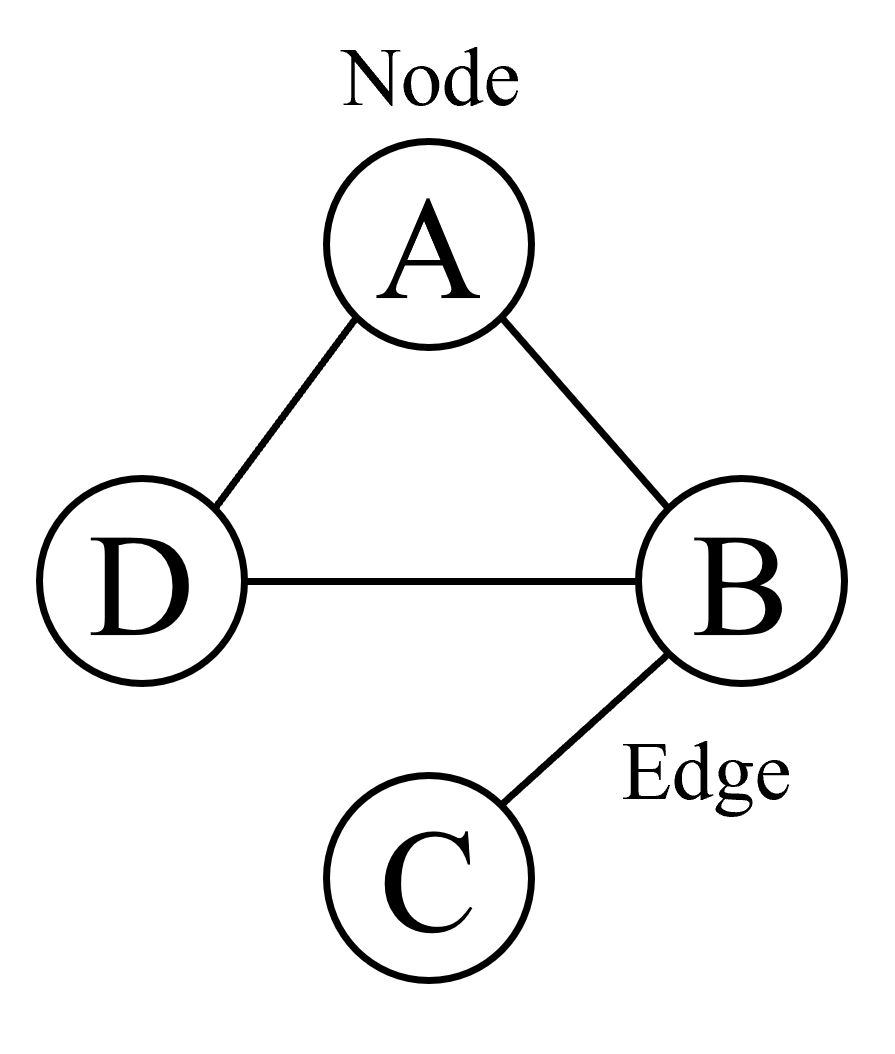

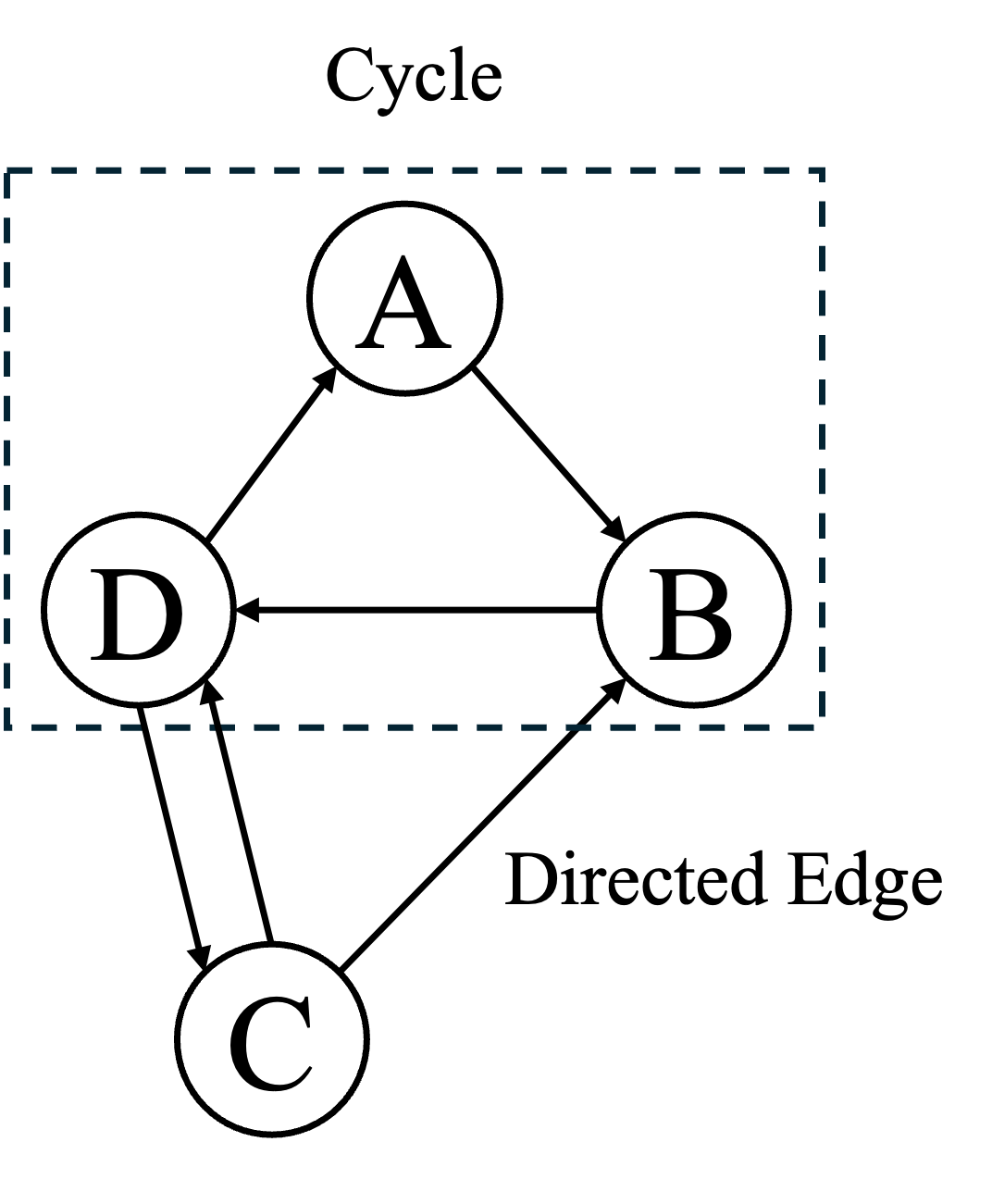

In Computer Science, trees are a type of graph. Graphs are collections of nodes and edges.

Edges can be directed or undirected. Directed edges can only be traversed in one direction, usually represented as arrows. Edges, i.e., connections between nodes, can form cycles. These cycles are paths that start and end with the same node.

Exercise 12.3 The diagram above highlights the cycle A→B→D→A. Can you find another cycle?

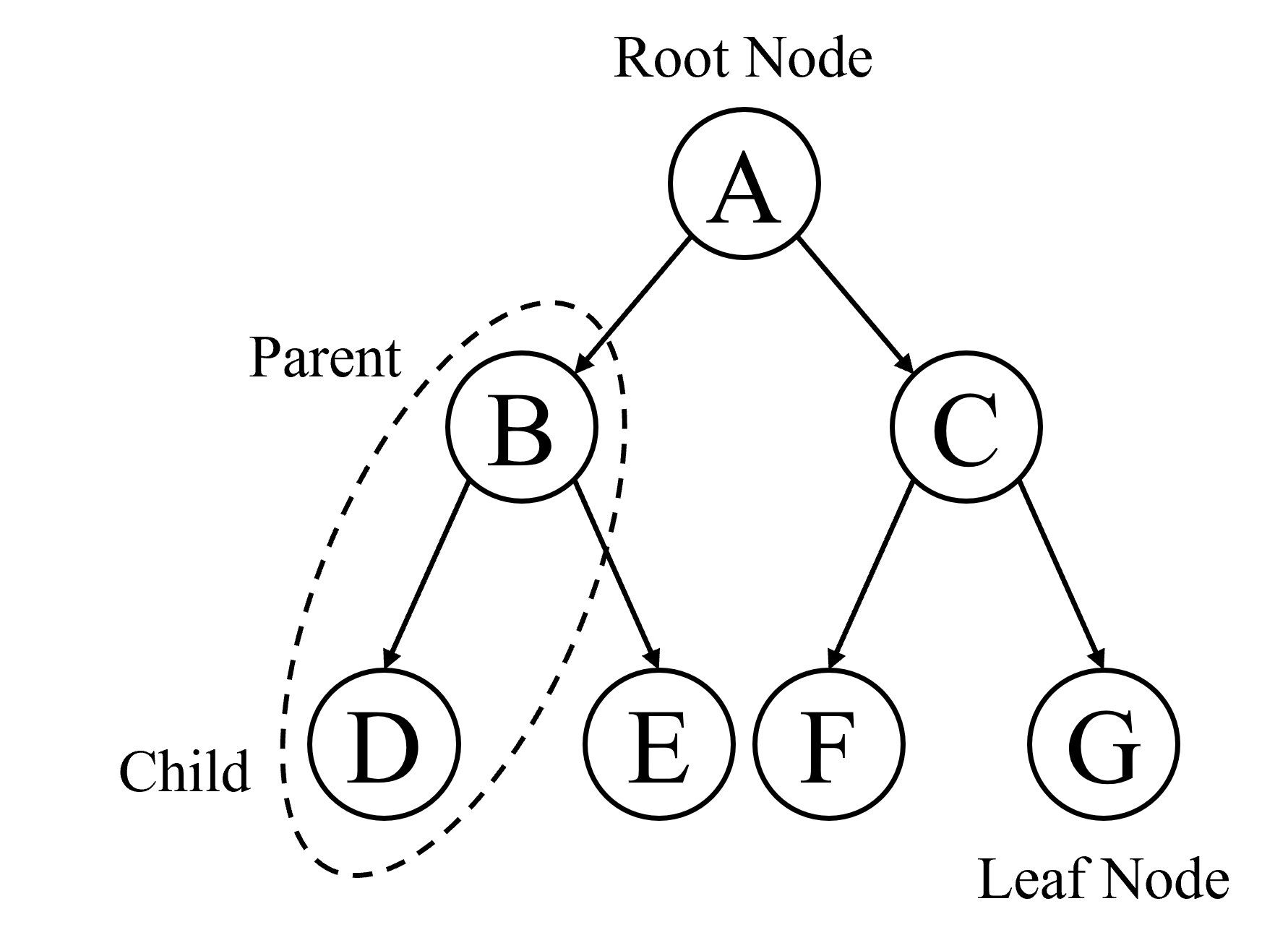

Trees are Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs). This is a bit of a mouthful, let’s take these terms one by one:

- Directed: They flow from the root to the leaves

- Acyclic: They do not contain any cycles; there is only a single path from the root to each node

Below is an example of a tree with seven nodes:

Trees, like all graphs, are composed of nodes and edges. In addition to the usual graph jargon, there are a few tree-specific concepts. To understand them, consider the example above:

- Parent and child nodes: both connected by an edge (nodes B and D)

- Root node: The topmost node of a tree (node A)

- Leaf node: A node with no children (node G)

Exercise 12.4 Find another example of:

- Leaf node

- Parent node

12.4 From Trees to Maps

Just like the KNN model, Decision Trees build a map from the input features to the target variable. Using a Decision Tree to generate predictions for all possible feature values, we get the following map:

12.5 Final Thoughts

That is it, we have built our first Decision Tree! We can use this model to predict any new observation based on its two features and position on the map above.

This is only a simple introduction to Decision Trees. The next chapters will explore the inner workings of this model family, starting with the evaluation of data splits. What makes a good split of a dataset?

12.6 Solutions

Solution 12.1. Exercise 12.1

- Observation 1: \(\circ\)

- Observation 2: \(\times\)

- Observation 3: \(\circ\)

Solution 12.2. Exercise 12.2

- Observation 1: \(\circ\)

- Observation 2: \(\times\)

- Observation 3: \(\circ\)

Solution 12.3. Exercise 12.3 There are many possible cycles, here are two examples:

- C→D→C

- C→B→D→C

Exercise 12.5 Solution. Exercise 12.5

- Leaf node: D, E, F, G

- Parent node: A, B, C